With my previous posts I started to write a serious of blogs with the heading “My journey with Institut Technik & Bildung (ITB)”. These blogs are intended to support the work (or follow-up) of the ITB “Klausurtagung” that will take place on Friday 9. December 2016. The inspiration to write personal blogs that deal with the history of ITB comes from the Klausurtagung 2015. With this series I try to compensate my absence due to health issues and to pass a message, wah has happened at different times and with different themes. In the first post I tried to cover my first encounters – my study visit in 1989 and participation in the Hochschultage Berufliche Bildung 1990 conference. In the second post I gave insights into the Modellversuch Schwarze Pumpe and to related European cooperation projects 1995 – 1999. In the third post I discussed the Europrof project, the Unesco International TVET meeting in Hangzhou 2004 and its follow-up. In the fourth post I will discuss the development of our work from the TTplus project to the European Consultation seminars on VET teachers and trainers in the years 2007 – 2010.

Remarks on the earlier history of the theme “Teachers and trainers in VET” at European level

My first encounter with the theme “Teachers and trainers in VET” at European level took place, when I was working in Cedefop (European Centre for the Drevelopment of Vocational Training) as a national seconded expert sent by the Finnish government. Cedefop was being relocated from Berlin to Thessaloniki, Greece and I had just got a new contract with which I would start as a temporary official of the EU in Thessaloniki. At that time the Cedefop project manager who was in charge of the newly started project “Teachers and trainers in VET” asked me to take over this project since she was leaving Cedefop and moving to Eurostat. For her this was a project to be completed when the national reports for all countries are completed.

When I had joined the project, I realised that there was a strong community-building process going on and that it should not be dropped. Yet, I had already got my activities in VET research cooperation started (accompaniment of European projects, joint synergy seminars with top projects, participation in European policy dialogue events with the projects) and I couldn’t concentrate sufficiently on the practitioner network. After a lengthy transition period another Cedefop project manager took over this project and managed the official launch of the TTnet network in 1998 (based on the preparatory work in the years 1995-1997).

From that point on the TTnet seemed to be the natural address to collect European studies and expertise on the theme ‘teachers and trainers’ However, there were two major limitations in the way that the network had been constituted. Firstly, following the Cedefop tradition, the network was built upon national contact points that coordinated the activities and eventually invited further actors. This was a somewhat exclusive mode of participation. Secondly, it was left to each country, whether the contact point is hosted by institutions for vocational teacher education or major training organisations (with ‘training the trainers’ activities) or national VET authorities. As a consequence, the national contact points covered the field from the perspective of their own priorities.

When the European Commission in the years 2005-2006 was looking for ways to analyse more closely the role of VET teachers and trainers as a target group for European policies, these measures were not crried out via TTnet but via new priorities in the Leonardo da Vinci programme and via specific tenders (which also were open for the TTnet members as well). From the thematic pointof view, special emphasis was given on measures that focused on in-company trainers or on trainers in specialised training organisations (beyond the initial VET). This was the background for the many parallel activities on the theme ‘teachers and trainers’ that were carried out by ITB in the years 2006 -2010: The Eurotrainer I survey, the TTplus project, the Consultation seminars and the Eurotrainer II network. Below I will focus on the TTplus project and the Consultation seminars in which I had a major role.

The TTplus project – approaches and initiatives

The TTplus project was set up with the ambitious heading ‘Framework for continuing professional development of trainers’ and building upon the experiences of the Euroframe project (see my previous post). The project took into account from the beginning the fact that the patterns for employing trainers (for workplace-based learning) and the respective arrangements for ‘training of trainers’ vary to a great extent. Therefore, The empirical work was based on three case studies to be carried ou in the particpating countries – then to be followed by policy analyses, reflections on the role of European Qualification Framework (EQF) and recommendations.

Concerning the policies and/or societal boundary conditions for engaging trainers and organising ‘training for trainers’ the case studies and policy analyses provided the following kind of group picture:

- In Germany the exisiting framework for training of trainers (AEVO) had been teamporarily suspended (in order to encourage the companies to take more apprentices. The companies that were studied were interested in supporting training of trainers – and used AEVO as a basis. Yet, they saw AEVO as minimum and were looking for more.

- In Portugal the partners studied private training providers who organised employment schemes commissioned by the employment services. The trainers’ aptitude certificate (CAP) required as minimum standard tended to reduce the pedadgogic room for manoeuvre to traditional frontal teaching.

- In Greece the companies studied were not subject to follow any government policies regarding in-company training – this was up to company-specific decisions. Likewise, it was up to the companies to engage trainers and to consider the competences of trainers from their perspectives. From the analyst’s point of view there was a case for a government intervention to to introduce minimum level training obligations and minimum standards for trainers.

- In Wales the companies contacted had outsourced most of their training activities and these were catered for by freelance-trainers who had developed their career as allrounders (from the content point) and as training technique specialists. Whilst they were in the position to outline frameworks for professional development (but were sceptical whether such frameworks should be applied to freelance trainers).

As these examples already indicate, the European landscape of training at workplace and ‘training of trainers’ was getting more colourful and it was not self-evident, how to promote European policies in an effective way. The approach of the project made it possible to get insights into the training contexts (companies, training providers, training arrangements) and to collect working issues. This all served as good preparation for the forhcoming European activities.

Analyses on the role of the European Qualification Framework(s) (EQF)

in the light of the above it was apparent that the ‘European dimension’ of the project TTplus was not to set common European standards for trainers – neither was there a case to declare a common recommendation for continuing professional development. Instead, the project provided an overview of the challenges and eventual steps forward in different countries (taking into account the organisational, institutional and policy contexts).

In this respect the analysis on the role of the problems in applying European Qualification Frameworks (EQFs) to the field ‘teachers and trainers in VET’. Whilst in several countries, VET teachers were educated in universities or higher education institutions, this was not the universal rule across Europe. In this respect the EQF for Higher Education (the Bologna process) provided the general framework. Yet, considering the career models of VET teachers, there was a tension between study programs for full-time students vs. professionals in the middle of career shift.

For the same reasons the European Qualification Framework for VET (or lifelong learning) did not provide an orientative framework for career progression – neither within the context of workplace training nor regarding career shift from training activities fro teacher duties. In this respect the German country report made transparent the initial discussion on such career models (and how to support them with different national frameworks). However, the discussion was at early stage and ITB got at that time linked with the developmental initiatives (after the TTplus project).

The consultation seminars – overall approach and insights into the workshops

In the light of the above it is interesting to note the opportunities provided by the Europe-wide Consultation seminars “VET teachers and trainers” in 2oo8 – 2009. This was a European Commission initiative to pull together knowledge and different stakeholders’ views via series of ‘regional’ workshops that cover all Members States, EEA partners and candidate countries. ITB won the tender with a consortium based on the Eurotrainer projects. The task was originally to organise six regional workshops to cover different European regions and to draw conclusions from hitherto implemented policies and intiatives for common European initiatives. The expectations were rather high regarding conclusions that could support incorporation of VET teachers and trainers into EQFs or under specific EU-level ‘communications’ (from the Commission to the European Parliament).

The workshops were designed as higly participative, interactive and collaborative events with quick shifts between differen kinds of sessions as the following:

- Statements on the wall: Collection of statements on the roles, tasks and development prospects of trainers – collected and grouped on the wall under respective headings – reflections on different positions and groupings.

- Witness sessions: Quick presentations on recent innovations/initiatives/pilots that the participants bring from their home countries – what were the strengths/weeknesses, what made them sustainable/fragile.

- Mapping European policies/initiatives: Participants were asked to fill in ‘problem’ cards, ‘method/measure’ cards and ‘policy’ cards to outline proposals. The groups collected and grouped the results.

- Priority ranking: Participants were asked to indicate European ‘priorities’ that had been high and should be kept high vs. had been high but should be lowered vs. had been low and should be topped up vs. had been low and should be kept low.

These were some examples of the activities that were managed in the workshops. Altogether they gave the participants a good feeling that their views were respected, their contributions were taken on boards and the the groups worked together. Indeed, as ‘regional’ and trans-national workshops for knowledge sharing and dialogue the events served very well. However, the problem was in brining the European policy level into discussion and developing the feedback processes in such a way that European policy-makers could draw conclusions for their work.

– – –

I think this is enough of the projects and activities of this period. They were rich learning experiences but showed major difficulties in working towards a European synthesis – and at the same time shaping recommendations for development activities in particular VET contexts. This challenge will be explored in the forthcoming blogs.

More blogs to come …

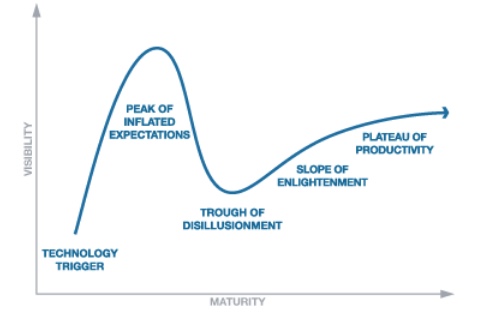

Has Learning Analytics dropped of the peak of inflated expectations in Gartner’s hype cycle? According to Educause ‘Understanding the power of data’ is still there as a major trend in higher education and Ed Tech reports a KPMG survey which found that 41 percent of universities were using data for forecasting and predictive analytics.

Has Learning Analytics dropped of the peak of inflated expectations in Gartner’s hype cycle? According to Educause ‘Understanding the power of data’ is still there as a major trend in higher education and Ed Tech reports a KPMG survey which found that 41 percent of universities were using data for forecasting and predictive analytics.