As promised some further thoughts on the DISCUSS conference, held earlier this week in Munich.

As promised some further thoughts on the DISCUSS conference, held earlier this week in Munich.

One of the themes for discussion was the recognition of (prior) learning. The theme had emerged after looking at the main work of Europa projects, particularly in the field of lifelong learning. The idea and attraction of recognising learning from different contexts, and particularly form informal learning is hardly new. In the 1990s, in the UK, the National Council for Vocational Qualifications (as it was then called) devoted resources to developing systems for the Accreditation of Prior Learning. One of the ideas behind National Vocational Qualifications was teh decoupling of teaching and learning from learning outcomes, expressed in terms of competences and performance criteria. Therefore, it was thought, anyone should be able to have their competences recognised (through certification) regardless of whether or not they had followed a particular formal training programme. Despite the considerable investment, it was only at best a limited success. Developing observably robust processes for accrediting such learning was problematic, as was the time and cost in implementing such processes.

It is interesting to consider why there is once more an upsurge of interest in the recognition of prior learning. My feeling was in the UK, the initiative wax driven because of teh weak links between vocational education and training and the labour market.n In countries liek Germany, with a strong apprenticeship training system, there was seen as no need for such a procedure. Furthermore learning was linked to the work process, and competence seen as the internalised ability to perform in an occupation, rather than as an externalised series of criteria for qualification. However the recent waves of migration, initially from Eastern Europe and now of refugees, has resulted in large numbers of people who may be well qualified (in all senses of the word) but with no easily recognisable qualification for employment.

I am unconvinced that attempts to formally assess prior competence as a basis for the fast tracking of awarding qualifications will work. I think we probably need to look much deeper at both ideas around effective practice and at what exactly we mean my recognition and will write more about this in future posts. But digging around in my computer today I came up with a paper I wrote together with Jenny Hughes around some of these issues. I am not sure the title helped attract a wide readership: The role and importance of informal competences in the process of acquisition and transfer of work skills. Validation of competencies – a review of reference models in the light of youth research: United Kingdom. Below is an extract.

“NVQs and the accreditation of informal learning

As Bjørnåvold (2000) says the system of NVQs is, in principle, open to any learning path and learning form and places a particular emphasis on experience-based learning at work, At least in theory, it does not matter how or where you have learned; what matters is what you have learned. The system is open to learning taking place outside formal education and training institutions, or to what Bjørnåvold terms non-formal learning. This learning has to be identified and judged, so it is no coincidence that questions of assessment and recognition have become crucial in the debate on the current status of the NVQ system and its future prospects.

While the NVQ system as such dates back to 1989, the actual introduction of “new” assessment methodologies can be dated to 1991. This was the year the National Council for Vocational Qualifications (NCVQ) and its Scottish equivalent, Scotvec, required that “accreditation of prior learning” should be available for all qualifications accredited by these bodies (NVQs and general national qualifications, GNVQs). The introduction of a specialised assessment approach to supplement the ordinary assessment and testing procedures used when following traditional and formal pathways, was motivated by the following factors:

1. to give formal recognition to the knowledge and skills which people already possess, as a route to new employment;

2. to increase the number of people with formal qualifications;

3. to reduce training time by avoiding repetition of what candidates already know.

The actual procedure applied can be divided into the following steps. The first step consists of providing general information about the APL process, normally by advisers who are not subject specialists, often supported by printed material or videos. The second and most crucial step includes the gathering and preparation of a portfolio. No fixed format for the portfolio has been established but all evidence must be related to the requirements of the target qualification. The portfolio should include statements of job tasks and responsibilities from past or present employers as well as examples (proofs) of relevant “products”. Results of tests or specifically-undertaken projects should also be included. Thirdly, the actual assessment of the candidate takes place. As it is stated:”The assessment process is substantially the same as that which is used for any candidate for an NVQ. The APL differs from the normal assessment process in that the candidate is providing evidence largely of past activity rather than of skills acquired during the current training course.”The result of the assessment can lead to full recognition, although only a minority of candidates have sufficient prior experience to achieve this, In most cases, the portfolio assessment leads to exemption from parts of a programme or course. The attention towards specialised APL methodologies has diminished somewhat in the UK during recent years. It is argued that there is a danger of isolating APL, and rather, it should be integrated into normal assessments as one of several sources of evidence.”The view that APL is different and separate has resulted in evidence of prior learning and achievement being used less widely than anticipated. Assessors have taken steps to avoid this source of evidence or at least become over-anxious about its inclusion in the overall evidence a candidate may have to offer.”We can thus observe a situation where responsible bodies have tried to strike a balance between evidence of prior and current learning as well as between informal and formal learning. This has not been a straightforward task as several findings suggest that APL is perceived as a “short cut”, less rigorously applied than traditional assessment approaches. The actual use of this kind of evidence, either through explicit APL procedures or in other, more integrated ways, is difficult to overview. Awarding bodies are not required to list alternative learning routes, including APL, on the certificate of a candidate. This makes it almost impossible to identify where prior or informal learning has been used as evidence.

As mentioned in the discussions of the Mediterranean and Nordic experiences, the question of assessment methodologies cannot be separated from the question of qualification standards. Whatever evidence is gathered, some sort of reference point must be established. This has become the most challenging part of the NVQ exercise in general and the assessment exercise in particular.We will approach this question indirectly by addressing some of the underlying assumptions of the NVQ system and its translation into practical measures. Currently the system relies heavily on the following basic assumptions: legitimacy is to be assured through the assumed match between the national vocational standards and competences gained at work. The involvement of industry in defining and setting up standards has been a crucial part of this struggle for acceptance, Validity is supposed to be assured through the linking and location of both training and assessment, to the workplace. The intention is to strengthen the authenticity of both processes, avoiding simulated training and assessment situations where validity is threatened. Reliability is assured through detailed specifications of each single qualification (and module). Together with extensive training of the assessors, this is supposed to secure the consistency of assessments and eventually lead to an acceptable level of reliability.

A number of observers have argued that these assumptions are difficult to defend. When it comes to legitimacy, it is true that employers are represented in the above-mentioned leading bodies and standards councils, but several weaknesses of both a practical and fundamental character have appeared. Firstly, there are limits to what a relatively small group of employer representatives can contribute, often on the basis of scarce resources and limited time. Secondly, the more powerful and more technically knowledgeable organisations usually represent large companies with good training records and wield the greatest influence. Smaller, less influential organisations obtain less relevant results. Thirdly, disagreements in committees, irrespective of who is represented, are more easily resolved by inclusion than exclusion, inflating the scope of the qualifications. Generally speaking, there is a conflict of interest built into the national standards between the commitment to describe competences valid on a universal level and the commitment to create as specific and precise standards as possible. As to the questions of validity and reliability, our discussion touches upon drawing up the boundaries of the domain to be assessed and tested. High quality assessments depend on the existence of clear competence domains; validity and reliability depend on clear-cut definitions, domain-boundaries, domain-content and ways whereby this content can be expressed.

As in the Finnish case, the UK approach immediately faced a problem in this area. While early efforts concentrated on narrow task-analysis, a gradual shift towards broader function-analysis had taken place This shift reflects the need to create national standards describing transferable competences. Observers have noted that the introduction of functions was paralleled by detailed descriptions of every element in each function, prescribing performance criteria and the range of conditions for successful performance. The length and complexity of NVQs, currently a much criticised factor, stems from this “dynamic”. As Wolf says, we seem to have entered a “never ending spiral of specifications”. Researchers at the University of Sussex have concluded on the challenges facing NVQ-based assessments: pursuing perfect reliability leads to meaningless assessment. Pursuing perfect validity leads towards assessments which cover everything relevant, but take too much time, and leave too little time for learning. This statement reflects the challenges faced by all countries introducing output or performance-based systems relying heavily on assessments.

“Measurement of competences” is first and foremost a question of establishing reference points and less a question of instruments and tools. This is clearly illustrated by the NVQ system where questions of standards clearly stand out as more important than the specific tools developed during the past decade. And as stated, specific approaches like, “accreditation of prior learning” (APL), and “accreditation of prior experiential learning” (APEL), have become less visible as the NVQ system has settled. This is an understandable and fully reasonable development since all assessment approaches in the NVQ system in principle have to face the challenge of experientially-based learning, i.e., learning outside the formal school context. The experiences from APL and APEL are thus being integrated into the NVQ system albeit to an extent that is difficult to judge. In a way, this is an example of the maturing of the system. The UK system, being one of the first to try to construct a performance-based system, linking various formal and non-formal learning paths, illustrates the dilemmas of assessing and recognising non-formal learning better than most other systems because there has been time to observe and study systematically the problems and possibilities. The future challenge facing the UK system can be summarised as follows: who should take part in the definition standards, how should competence domains be described and how should boundaries be set? When these questions are answered, high quality assessments can materialise.”

This article was originally published on the

This article was originally published on the

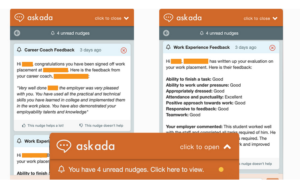

Formative assessment should provide a key role in all education and particularly in vocational education and training. Formative assessment can give vital feedback to learners and guidance in the next steps of their learning journey. It can also help teachers in knowing what is effective and what is not, where the gaps are and help in planning learning interventions.

Formative assessment should provide a key role in all education and particularly in vocational education and training. Formative assessment can give vital feedback to learners and guidance in the next steps of their learning journey. It can also help teachers in knowing what is effective and what is not, where the gaps are and help in planning learning interventions.